- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- SubscribeSubscribe

- Buy Now

A visit to Dilli Haat unfurls almost every traditional art and craft tradition from India. As you walk into the sprawling complex, state and national award-winning artisans can be seen hard at work making wares, greeting customers, and laying out a colourful storm. But a certain style of painting seemed to be missing from the 100-plus stalls&mdashthat of Bihar&rsquos sanjhi art.

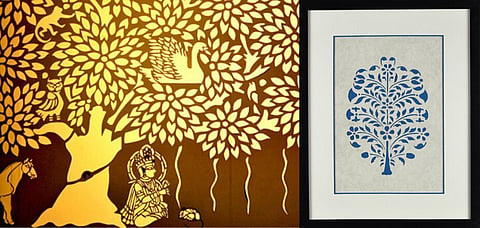

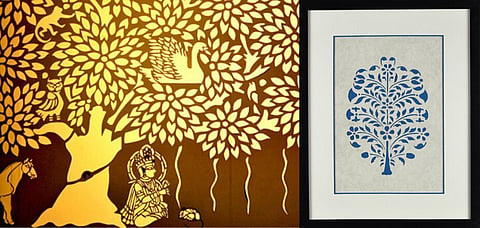

A paper cutting tradition originating from Mathura and Vrindavan, sanjhi artisans make ornate stencils that are then filled with natural powdered dyes. While the final, rangoli-style image used to be the star of the show, the stencils today are seen as pieces of art in their own right. With a ritualistic past, sanjhi paper cutting today makes its way into lamps, room patterns, stationery and even photo frames.

Ram Soni comes from a family in Mathura that has been entrenched in this painstaking yet beautiful tradition for over 350 years. Now based out of Alwar in Rajasthan, he is one of the award-winning artisans who will be taking visitors through this slowly fading craft at India Craft Week 2019. We caught up with the man behind the myth (pun, absolutely intended)...

What is the background of sanjhi art

Sanjhi art has been prevalent long before the Mughals came to India. The story goes that during the time of the Mahabharata, when Indraprastha was created, artisans from all over were invited to demonstrate their craft, among which sanjhi also found a place. The Kauravas came to see the new city themselves, and while looking around, Duryodhan fell into a pool of water. It is said that a sanjhi design was then seen floating on the surface above him. Yes, you can make sanjhi designs (called &lsquojal sanjhi&rsquo) on still water It is made in the same way it is created on walls. Then there is the 15-day Sanjhi Festival, celebrated to honour our ancestors, where we pay tribute to Krishna. Throughout this time, we hand cut all of his leelas on paper, which are then ceremonially displayed at temples in the evening, a little after 4pm. Sanjhi comes from the word for dusk.

Could you briefly take us through your inspiration when designing motifs, and the process of making one of the stencils

We use the art form to depict what is seen around us. For example, if we make it during the month of saavan, then we observe the kind of flowers and trees flourishing in that season, or the birds and animals migrating in, and incorporate them with great detail into the paper cuts. But when you delve into it, you also need to capture the emotion of a scene&mdashthe joy of Krishna&rsquos birth, Vasudev&rsquos journey across the torrents, etc. Critical thought&mdashoften for a long period&mdashis important. Then, we make a rough drawing of the scene, and begin cutting. Naturally, thinking about the artistic and practical qualities of making a 25-foot tree will take longer than generic, smaller designs. Making it look natural also takes time. The cutting is not the most crucial part of the process.

Has the art form changed over time

The sanjhi art displayed by the Vallabha Sampradaya (a Hindu Vaishnavite sect) has been unchanged ever since its inception. Most temples dedicated to Krishna also stick to traditional patterns, but there is still space for customisation. A patron in the past asked for an image of the Buddha, while another asked for Hanuman, both of which we have delivered.

India&rsquos tryst with metallurgy&mdashiron, copper and the like&mdashhas been long. To cut the designs on paper, initially something called the nunni, a metal nail clipper, was used. Burning incense sticks were also used to mark out patterns, as were knives. It was my family that actually invented the specific metal scissors that are used to make sanjhi art today.

How was sanjhi art influenced in the Mughal era Were new motifs or patterns introduced

Persian-influenced sanjhi designs were aplenty during their era, and some, like jaali work, are commonly used even today. Geometrical designs, certain flower motifs, the concept of the tree of life, they were all passed onto us from Persian artistic inclinations. My ancestors would tailor-make the stencils according to specific requests from Mughal patrons. But the base and spirit of sanjhi art still remained linked to indigenous ideas.

Is sanjhi art today still majorly linked to devotion How could it be popularised in urban India

Well, you cannot weave in religion everywhere, so we use nature motifs a lot today. It increases the chances of appealing to buyers from different backgrounds. After all, all religions are rooted from similar ideas of appreciating the environment and what is in it. Only today has segregation and labels become the most important factor. But nature&rsquos beauty is universal.

What has been the most memorable moment in your career

I think it is the diverse opportunities that have arrived over the years. Sanjhi paper cutting was initially about personal devotion and excellence in expressing it. Then came in customised work according to a client&rsquos demands. Seeing the joy on their faces, where we have been able to match their mental picture, is always memorable. Then we began working on Western-inspired designs, and it was challenging but rewarding. I have been doing this for 30-odd years, and the changes keep things interesting.

You can try your hand at this painting tradition under Mr Soni&rsquos guidance at the Sanjhi Paper Cutting Workshop tomorrow (11am-5pm) at India Craft Week. Tickets can be booked here.