- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- SubscribeSubscribe

- Buy Now

Huge forts are not uncommon in India but are usually associated with great kings, mighty warriors, or sizeable defending garrisons. Imagine a fort where a solitary person thwarted an enemy attack—or at least delayed. A woman. A woman who was not one of India’s famed warrior queens but a housewife.

The fort in question is Chitradurga, in the heart of Karnataka. During the 1770s, it was under the rule of a Nayaka chieftain. Hyder Ali, who then controlled the Kingdom of Mysore, coveted this strategically located stronghold. Not only was the fort powerful enough to repel an assault, but it also had a well-trained garrison in place. One member of that garrison was Thalege Bandhu Odhedu Sayisu. He was reportedly on guard one day in a quiet corner of the massive fort.

His wife, Obavva, came to deliver his meal. While he ate, she walked to a nearby pond by the fort wall to fetch water. That’s when she noticed something unusual—someone was attempting to squeeze through a gap in the rocks. Instead of screaming or panicking, Obavva reached for a pestle—called an onake—and struck the intruder. She killed him. Then another appeared. And another. As the story goes, she killed them all, one by one.

Later, she was found surrounded by dead bodies, holding the bloodied pestle. Obavva herself died later that day, but not before halting the intruders—soldiers from Hyder Ali’s army—who were attempting to infiltrate the fort in stealth.

The heroic woman became known as Onake Obavva, immortalised in Kannada popular culture through films, statues, and stories. The crack in the rock she defended is today known as Onake Obavvana Kindi. However, one must look at the fort's structure to understand why Hyder Ali’s men tried creeping in through such a narrow crevice instead of launching a frontal attack.

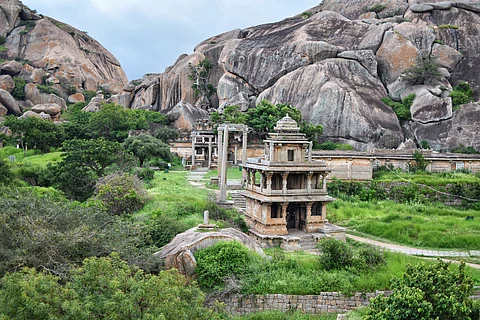

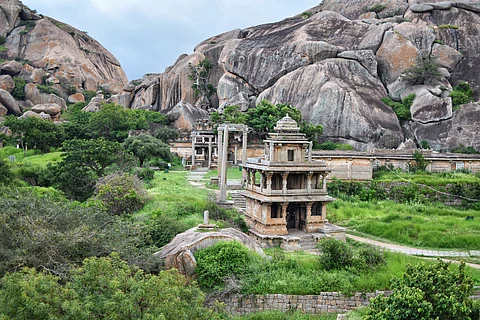

Locally called Elusuttina Kote—meaning ‘Fort of Seven Circles’—Chitradurga Fort was a marvel of medieval military architecture. At its prime, it had 19 gateways, numerous postern and secret gates, and even some nearly invisible entrances. The seven concentric fortification walls—three at the base and four rising higher—formed formidable lines of defence, each with solid stone bastions. The three outer circles even had moats.

An attacking force that managed to breach one level would face a deadly barrage from the next. Small wonder Hyder Ali’s troops attempted stealth instead of siege.

Today, however, the days of fire and arrows are long gone. Visitors enter the fort with a ticket, not a battering ram. A few guides wait near the entrance to walk you through the ruins. The stone walls still tower imposingly, offering glimpses of how formidable the place must have once been.

Historians trace the fort’s earliest occupation to the Hoysala dynasty, between the 11th and 13th centuries CE. Over the centuries, several rulers, including those of the Vijayanagara Empire, expanded it. Today, we see largely the legacy of the Nayaka rulers, once Vijayanagara feudatories who declared independence after the empire’s decline. Though Obavva’s heroics thwarted Hyder Ali’s initial attempt, he captured the fort in 1779. What remains today is a vast and evocative ruin.

The fort is dotted with temples: Hidimbeshwara, Sampige Siddeshwara, Ganesha, Anjaneya, and Gopalaswamy, among others. The Gopalaswamy Temple stands out with its statue of Krishna, flute in hand, flanked by cows and female attendants.

Another signature feature is the network of artificial water reservoirs, an ingenious system designed to withstand long sieges. Tanks and ponds dot the complex, many of them interconnected. One notable example is the Akka-Thangi Honda—the twin sister tanks—hewn from rock and fed by overflow from higher tanks like the one near Gopalaswamy Temple. Once full, these tanks channelled the water down to even lower reservoirs. It’s a timeless lesson in water management, relevant even today.

Strangely, the royal palace complex—once home to rulers—is in poor condition. Difficult to reach, hidden behind thorny vegetation, and mostly in ruins, the former palaces, granaries, magazines, wells, and gardens now lie neglected. Access requires some clambering and care.

Chitradurga’s history doesn’t end at the fort gates. Just outside town is Chandravalli, a site that takes us back over a millennium. Here, one finds inscriptions dating to the 4th century CE, a cave temple of Panchalingeshwara, and the eerie underground labyrinth of Ankalimatha, where torches are a must. One can easily get lost in the dark, meandering tunnels.

Further afield lies Brahmagiri, home to more ancient temples and a rock edict of Emperor Ashoka from the 3rd century BCE—a reminder that this region has been historically significant for over two millennia. Compared to these ancient echoes, the Chitradurga Fort itself seems positively modern.

Chitradurga—literally “Picturesque Fort”—is often bypassed by travellers heading from Bengaluru to Hampi. But within its boulder-strewn walls lies a heritage treasure trove, a landscape shaped by kings and queens, soldiers and saints, strategists and solitary heroes.

And perhaps most remarkably—by a housewife with a pestle who dared to stop an army.

Chitradurga Fort is around 200 km from Bangalore and can be reached easily by bus, train, or car. KSRTC buses, including luxury Airavat coaches, run frequently from Bangalore, taking about 3–4 hours. From the Chitradurga bus stand, autos or a short walk will get you to the fort. Direct trains also connect Bangalore and Chitradurga, with a travel time of roughly 5 hours—check online platforms for schedules. If driving, take NH4 via Tumakuru for a scenic 3-hour journey. Parking is available at the fort’s base, making it convenient for self-drive travellers.

The ideal time to visit Chitradurga Fort is between October and February, when the weather is cool and pleasant, perfect for exploring the vast fort complex on foot. Temperatures during this period range from 15°C to 28°C, making it comfortable to climb and walk around. Early mornings are especially recommended for panoramic views and a quieter experience. Avoid visiting during the summer months (March to May) as it can get extremely hot, with temperatures soaring above 35°C. The monsoon season (June to September) brings some greenery but also slippery paths, so caution is advised.