- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- SubscribeSubscribe

- Buy NowBuy Now

"India is a beautiful country with its beauty unknown to its own people," said Neville Tuli, founder of the Tuli Research Centre for India Studies in an exclusive interview with Outlook Traveller.

The centre organised the third edition of "Self discovery via rediscovering India," a photo exhibit that showcases select highlights of India's photographic history, curated by Tuli himself.

From Darogah Abbas Ali's rare photograph of Umrao Jan to R.R. Bharadwaj's shot of the Teli ka Mandir in Gwalior (the only temple in the country dedicated to an oil merchant), the exhibit captures the essence and beauty of the country through visuals captured across centuries.

With each photograph, you will be transported from the ghats of Benares and the sets of a Satyajit Ray film in Calcutta to admiring the beauty and majesty of the Taj Mahal.

There is something peculiar about the ghats of Benares. It’s in this peculiarity that one finds the beauty of the city.

As you witness the ghats come alive with the Ganga aarti and devotees taking a dip in the holy waters, you’ll see a son cremating his father’s body only steps away, as though life and death confront each other on the banks of the sacred river.

A representation of this duality in Benares’ nature is encapsulated in these two photographs. While Samuel Bourne’s photograph from the mid-1860s captures the burning ghat, the other photograph represents Benares as a city of grief and darkness.

One often talks about Bombay [now Mumbai] and Bollywood in a single breath. While the city is home to Hindi cinema, it is much more than that; it is also about people who live detached and fast-paced lives. Here are two photographs representing this nature of Bombay life.

The first is a 1938, rare silver gelatin print from the preview of the art-deco designed Metro cinema. The second, a photograph by Namrita Bachchan, represents how the distance between two people in Mumbai is greater than the distance between them and the buildings.

Delhi’s architecture tells a tale of time. A power centre of many erstwhile empires, the city has endured and adapted many changes. The first photograph by Charles Shepherd from 1870 shows a group of moulders creating casts at the Qutub complex. These casts, once completed, would be displayed in British museums.

The next is a set of 36 photographs by Madan Mahatta. These images capture the Nehruvian nation-building project from the 1950s and 60s. This was a time when the newly-elected Prime Minister of the country employed his modernist vision to the architecture of the capital’s buildings.

These buildings were commissioned to Indian architects, many of whom were sent to MIT and Harvard to study under the tutelage of Walter Gropius. This resulted in Bauhaus aspects to many of their designs, which features functional shapes, holistic designs, and basic industrial materials like concrete, steel, and glass.

The architecture of the city that once stunned the British was now being modernised using foreign designs and techniques, a full circle moment for New Delhi’s architecture!

Here are two photographs by R.R. Bharadwaj. The first is of the pristine Himalayas representing the India we once received. The second is a photograph of a factory in Jamshedpur, shot during a time when the nation was celebrating its industrial successes while beginning to toy with the country’s resources to bring her to its present state.

Calcutta gave the world one of the finest filmmakers in the history of world cinema, Satyajit Ray. Ray and Calcutta were inseparable. Here, he not only spent most of his life, but also shot most of his movies.

For instance, in “The Calcutta Trilogy”—“Pratidwandi,” “Seemabaddha,” and “Jana Aranya”—he captured the social and political turmoil that the city underwent at the time.

These are photographs by Nemai Ghosh, who is known to have created a visual biography of his beloved “Manik da.”

The life of a photograph is long. The first picture here is an 1871 albumen print by the V. & E. Pont studio in Lucknow’s Chattar Manzil or umbrella palace. The palace was built for the rulers of Awadh and their families on the banks of the Gomti river.

The second photograph is a poster released by the Government of India nearly 80 years later in the 1950s for their “See India” campaign. Printed by Bolton Fine Art Litho Works, the poster was aimed at promoting tourism in the country.

It is an example of how photography and lithography are used to represent the beauty of Lucknow.

The Hoysaleswara Temple or the Great Temple of Hullabeed is one of the many architectural marvels of India. The intricately detailed sculptures in Hullabeed were chiseled from soft sandstone.

These are photographs, captured by William Henry Pigou in the mid-19th century, are from a time when the British were trying to learn more about the country to assert their rule.

Beyond cementing a moment in time, these photographs are also a reminder to appreciate and value the architectural richness and detail of our own country.

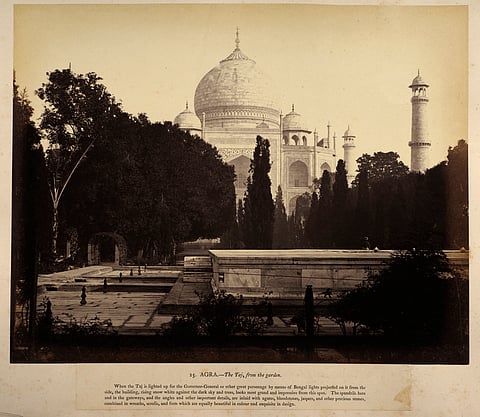

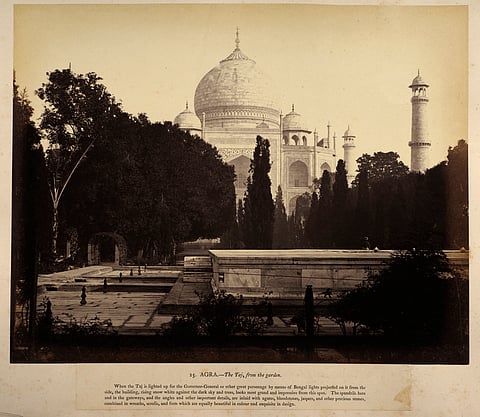

These are Eugene Clutterbuck Impey’s shots of the majestic Taj Mahal as captured in the early 1860s from a different perspective. While the monument stands in the background, it finds its way to draw one’s eye towards it. Such is the splendour of the Taj.