- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- SubscribeSubscribe

- Buy Now

Tucked away amidst the towering peaks of the Himalayas is a valley called Spiti. A cold desert with rugged but the most breathtaking landscapes, Spiti is home to Buddhist monasteries, with their whitewashed walls clinging to the cliffs, like a sentinel of time, guarding centuries of wisdom and devotion. In this valley, time moves at its own pace. It is a world unto itself, untouched by the events and rhythms of the outside world. Here, everything operates according to its own rules, traditions, norms, and its own sense of order. One such traditional practice that exists here is called the Amchi system.

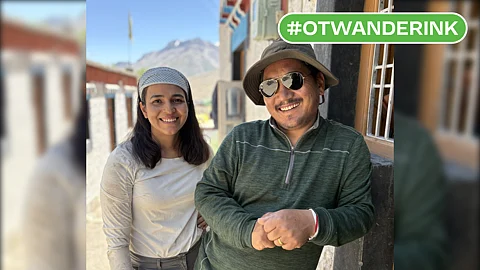

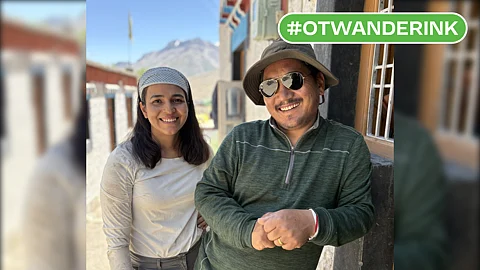

In a world where medicine and healthcare are advancing like never before, the people of Spiti still do not have access to basic healthcare. But they do have access to something that you and I don’t—their beloved Amchis. Amchi is a title for a traditional Spitian doctor who diagnoses illnesses simply by reading your pulse and I had the privilege of meeting one of the few surviving Amchis in the valley—Chhering Norbu (Smanla Khang Gyu ngul).

Chhering Norbu or Norbu ji, as I fondly addressed him during my time there, is a man of many talents. He belongs to a family of Amchis from the Demul village and is one of the few remaining Amchis in Spiti. Ever since Norbu ji was a child, he was taught by his grandfather, his father and various other senior Amchis from the valley, about the illnesses and ways to diagnose them. Norbu ji would also go on day hikes with them, with his Kodak camera to understand the identification and use cases of different medicinal plants in the valley. He then went on to master the Sowa Rigpa (Ancient Science of Healing) from Dharamshala, and at 22, he was all set to become one of the youngest amchis in the valley.

Yet his path to becoming the valley’s healer wasn’t without its trials. It was a journey shaped as much by loss as it was by the unwavering belief of his community

Norbu ji’s father passed away about two years after he started practicing as an Amchi. With his father gone, there was a sudden lack of guidance, purpose and direction. Disheartened and discouraged, Norbuji and his wife decided to move to Kaza, a spot which was just starting to grow as a tourist destination back then. But, as life would have it, things didn’t go as planned.

That winter, when they were visiting their families in Demul, a little girl suddenly fell ill. Her parents panicked and came running to Norbuji for help. He rushed to their house and found a crowd of villagers there, along with their village deity. Everyone looked tense, until Norbuji checked on the girl and told them that she was going to be fine. There was immediately a collective sigh of relief. That evening, the village deity turned to him and said, “You need to continue this practice. If you stop, who will these people turn to in times like this?” The village deity encouraged everyone to go to Norbuji for their checkups. What happened the next day was a pleasant surprise. The whole village gathered and held a big ceremony. They officially announced Cherring Norbu as their next Amchi and from that day on, Norbuji never looked back, and served his community each day.

In conversation with him, he talked about the ancient science of Sowa Rigpa and the dying practice of amchis in the valley. He told me how Sowa Rigpa came into being about 2500 years ago, when Shakyamuni Buddha manifested the medicinal form of himself while meditating in a forest. “The Medicine Buddha is a form through which Shakyamuni reveals his healing teachings. He is regarded as a prominent figure in this ancient Tibetan practice.” said Norbu ji. Shakyamuni came up with the concept of Sowa Rigpa and the four tantras.

“The knowledge of the Sowa Rigpa was initially only passed on by lineage. But by 1916 the 13th Dalai Lama urged the people of the valley to safeguard the tradition by formalizing it into a structured course, which is now taught at Men-Tse-Khang, Lhasa in Tibet. It was re-established 1961 in Dharamshala and with the institute coming in, people outside of the Amchi lineage also started learning about the practice. That’s also where I trained from.”

Norbu ji then went on to tell me about the four tantras. Initially, I thought these were some chants or sounds, until Norbu ji explained that the four tantras were not chants but the foundational texts of Tibetan medicine. These tantras covered the core principles, theory, diagnosis, and treatment methods of Sowa Rigpa. “At the institute, you get to study each of these texts for a year before entering your fifth year. In the fifth year, you have to practice under a senior Amchi and the only way to pass is to get 98% of your day’s readings correct. If your score is below 98%, you’re sent back to study the tantras for another year.” explained Norbu ji.

“What is the difference between the four?”, I asked.

“The root tantra or rTsa rGyud, which is the first tantra, tells you the types of illnesses—both in present and future times and in humans and animals alike. The first tantra also predicted the COVID-19 pandemic, years before it happened. It discusses the imbalances in the body caused by the different elements—air, fire, water, earth and space. The second tantra, which is called the Explanatory Tantra or bS`ad rGyud, delves deeper into ways of identifying these illnesses through different methods like pulse reading, urine observations and genetic history. The third tantra, known as Oral Instruction or Man ngag rGyud, helps the student focus on the practical application of the first two tantras. And the last, but the most crucial of all is the Subsequent Tantra or the Phyi ma rGyud, which focuses on the identification of medicinal plants and the making of medicines. It tells us which medicine to use for what and the quantity that should be prescribed to a patient.”

“During my father’s time as an Amchi, there used to be about 24 Amchis in this valley. Now there are only 4-5 practicing ones.” On asking him more about why this was the case, he explained that the Amchi system works on barter. In the Buddhist tradition, being an Amchi is seen as a noble calling, so charging money isn’t really accepted. Instead, people give what they can in return—maybe a sack of rice, or help when you need it. It’s about mutual support and respect within the community more than any financial exchange. “That’s why a lot of young people are stepping away from it now. There aren’t many ways to earn cash in this valley, and being an Amchi, you don’t just contribute your time but also cover the cost of medicines. Sourcing raw materials for these medicines is an expensive and tedious affair, because many of the herbs grow in specific altitudes and climates. In some cases, we have to trek for hours or even days, into remote areas to find the right plants. Plus, with growing demand and changing environmental conditions, certain herbs are becoming harder to find, which drives the cost up even more, and not everyone can afford to pay for it out of their own pocket, especially if they come from modest backgrounds.” said Norbu.

On asking him about the official recognition or support that Amchis receive from the government, he mentioned that the Ministry of Ayush recognises Amchis and has also set up a Sowa Rigpa institute in Ladakh to promote quality education and research facilities.

“You said that the Sowa Rigpa practice is usually passed on from generation to generation. What happens to lineage Amchis if there is no successor?” I asked. “Usually the knowledge of Sowa Rigpa is passed on from the father to the eldest son in the family. In recent times, daughters have also started learning and carrying on this practice, as part of their lineage. And if there isn’t a direct heir, which is rarely the case, the knowledge usually gets passed along to other children in the extended family.”

“What keeps you going, Norbu ji?”

“I come from a family of Amchis and I’ve grown up watching my elders dedicate their lives to healing others with deep knowledge, compassion, and a strong sense of duty. For us, this isn’t just a profession but a way of life, a tradition that has been passed down through generations. I feel a deep sense of responsibility to keep this tradition alive. It’s a way of honoring my ancestors, serving my community, and making sure this precious knowledge doesn’t fade away.”

In my conversation with Norbu ji, I felt the weight of the knowledge he had worked so hard to preserve. He was rooted in compassion and a deep sense of duty, which made me think on how far we’ve drifted from a world where values like empathy and responsibility once guided our actions, to the one that’s driven by profits and stacks of money. Meeting Chhering Norbu was not just a lesson in ancient medicine, but a profound reminder of the quiet resilience that still pulses through the veins of remote communities like Spiti. In a world increasingly defined by speed and technology, the Amchi system stands as a testament to a slower, deeper kind of wisdom, one rooted in nature, tradition, and compassion. As modern healthcare continues to evolve, perhaps there is something to be learned from the enduring spirit of healers in Spiti, who serve not for profit, but for purpose. Their knowledge may be ancient, but its relevance feels more urgent than ever.