- Destinations

- Experiences

- Stay

- What's new

- Celebrating People

- Responsible Tourism

- CampaignsCampaigns

- SubscribeSubscribe

- Buy Now

It was a day in April of 1947 that a Norwegian explorer and ethnographer, Thor Heyerdahl, brought a tale so often told in seafaring lore and circles to life. First, he launched an experiment that would captivate the world: could people from pre-Columbian South America have crossed the Pacific Ocean on a primitive raft and reached Polynesia? Then, with no advanced navigation systems and using only the same materials available to ancient mariners, Heyerdahl and his crew built a balsa-wood raft named Kon‑Tiki and set sail from Peru. What followed then was a tale in no lack of thrill and wonderment—one that an ancient mariner could grip you and narrate even as you are at the threshold of a wedding: a 101-day, 4,300-mile odyssey that challenged and toppled conventional theories of human migration and turned into a landmark in experimental archaeology. Here’s an in-depth look at the man, the voyage, and its enduring legacy.

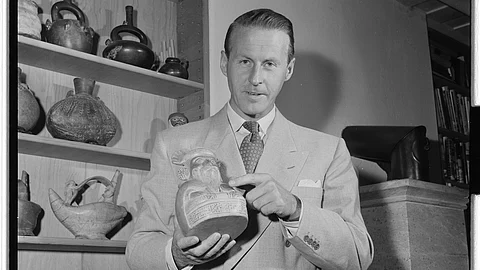

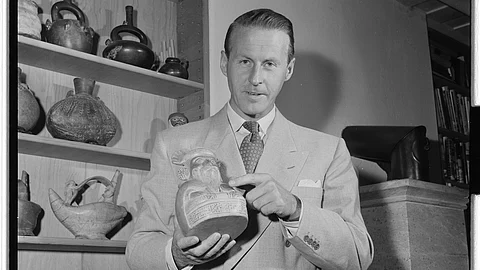

Born in Larvik, Norway, in 1914, Thor Heyerdahl inherited a university training, turning into a man of versatile vocations with specialisations in zoology, geography and ethnology in Oslo. The Norwegian’s work in Marquesas Islands in the late 1930s sparked a radical hypothesis: Polynesia might have been settled by voyagers from South America. Though thoroughly disregarded by many scientists of the time, Heyerdahl's theory led him to plan an audacious test—recreate an ancient raft using only indigenous materials and drift westward across the Pacific.

Balsa logs were gathered from Ecuador and Peru, adhering strictly to historical raft construction methods; nine large logs were assembled, 13 to 14 metres long each, and lashed together with hemp ropes—no nails or modern fastenings were used. The crew included five men: engineers, radio specialists, a navigator and an anthropologist. A parrot named Lorita was also company to the crew. The raft carried 275 gallons of water in bamboo containers, 200 coconuts, root vegetables, fishing gear and US Army rations. Navigation relied on the Humboldt Current and prevailing winds.

It was on 28 April 1947 that Kon-Tiki departed Callao, Peru. Despite initial scepticism, the raft persevered through massive waves, relentless weather and shifting current. Once several weeks had passed, they had drifted into the South Equatorial Current and maintained an average speed of 1.5 knots. Along the way, fishing regularly, capturing flying fish, tuna, squid and more made for the crew's pastime. Notwithstanding extreme weather conditions, the raft buoyed and proved seaworthy and unbroken.

Later on August 7, completing 101 days at sea and covering nearly 4,300 miles, Kon-Tiki struck a reek and touched ground on Raroia Atoll in the Tuamotus. All the six men in the crew survived and were rescued by island inhabitants. The success of the voyage, while not confirming Heyerdahl's theory of Polynesian origins, proved that long-distance ocean crossings on primitive vessels were physically feasible.

Following these reality-defying events, Heyerdahl's book, The Kon‑Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas, was published in 1948 to a warm reception, selling out within weeks, and was later translated into more than 70 languages. Heyerdahl also went on to direct a documentary subsequently which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1951. The journey also inspired similar expeditions, including Heyerdahl's reed-boat voyages (Ra II in 1970) in addition to influencing experimental archaeology and storytelling about ancient seafaring.

While mainstream archaeologists maintain Polynesia’s origins lie in Island Southeast Asia, genetic studies—such as the detection of South American markers in Easter Island populations—have introduced nuance to Heyerdahl’s ideas, even if fully supporting his theories remains controversial.

Over the years, Kon-Tiki turned into an icon of adventure and daring. The original raft is on permanent display at the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo, which opened in 1949 and now attracts thousands of visitors annually. In 2012, a dramatised feature film revived global attention to the event, reintroducing Heyerdahl's voyage to a new generation. Furthermore, DNA research in the 2020s has revived discussion on trans-Pacific contact, adding scientific context to Heyerdahl's pioneering experiment.